What’s common between the first verse of Mahabharata and the last verse of Mēlputtūr Nārāyaṇa Bhaṭṭatiri’s Narayaneeyam written in 1586 CE.?

The first verse of adi parva reads

नारायणं नमस्कृत्य नरं चैव नरॊत्तमम देवीं सरस्वतीं चैव ततॊ जयम उदीरयेत

(” Om ! Having bowed to Narãyana and Nara, the most exalted male being, and also to the Goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered)

Mēlputtūr Nārāyaṇa Bhaṭṭatiri’s Narayaneeyam ends with the words ayur- ̄arogya-saukhyam. This wishes long life, health, and happiness to the readers of his devotional poem.

The words jayam and ayur- ̄arogya-saukhyam have two properties.

- Both have proper meanings in the context of the sentence used (as in, they are not gibberish words.) This matters as we go into the details.

- The second property is not well known. Both those words encode a number that has a deeper meaning.

In this system of encoding, jaya represents 18 and ayur- ̄arogya-saukhyam 17,12,210. Counting those many days from Kali Yuga, gives the date as 8th December 1586, the completion date of Narayaneeyam.

This article looks at this style of representing numbers using meaningful words.

Katapayadi Number System

Process-wise, the encoding is simple. Each Samskritam consonant is given a number. Hence the algorithm is as simple as reading it from right to left.

| ja | ya |

|---|---|

| 8 | 1 |

The letter ja is assigned the number 8 and ya, 1. Reading from right to left, it becomes 18.

Why did Vyasa pick on the number 18 and encode it as jaya? Why did he call Mahābhārata as jaya. Mahābhārata has 18 parvas. Gita has 18 chapters. The war was fought for 18 days. There were 18 akshauhini’s in the war. Thus jaya was not a random selection.

Here is the full table of the consonant to number assignment.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 |

| ka क ക | kha ख ഖ | ga ग ഗ | gha घ ഘ | nga ङ ങ | ca च ച | cha छ ഛ | ja ज ജ | jha झ ഝ | nya ञ ഞ |

| ṭa ट ട | ṭha ठ ഠ | ḍa ड ഡ | ḍha ढ ഢ | ṇa ण ണ | ta त ത | tha थ | da द ദ | dha ध ധ | na न ന |

| pa प പ | pha फ ഫ | ba ब ബ | bha भ ഭ | ma म മ | |||||

| ya य യ | ra र ര | la ल ല | va व വ | śha श ശ sha ष ഷ | sa स സ | ha ह ഹ |

Look at the letters which represent the number 1. ka, ta, pa, ya gives it the name katapayadi (adi in Samskritam means beginning). Vowels meant 0, and vowels followed by a consonant had no value. In the case of compound letters, the value of the last letter was used.

In its land of origin, Kerala, it was known by a different name Paralpperu where paral means seashell and peru name” (astronomical calculations were done using seashells).

Here is another example. The year 2010 is expressed as natanara.

This is because

| Letter | Value |

|---|---|

| na | 0 |

| ta | 1 |

| na | 0 |

| ra | 2 |

If you read this backward, you get 2010. An important point is that the letters are not chosen randomly. They mean something. In this case, natanara means “a man (nara) who is an actor ( nata)”. Since there are many possible letters for each number, the mathematician can create a meaningful word from the numbers.

Similarly, ayur- ̄arogya-saukhyam represents 17,12,210 to represent the date of 8 December 1586. Why was the epoch chosen as the beginning of Kali Yuga? It was the popular way of dating events called the Kali-ahargana. Kali-yuga started at sunrise on Friday, 18 February 3102 BCE, and computing the number of days from then was common in planetary calculations.

The fact that Bhaṭṭatiri used this system is not surprising. He was a student of Achyuta Pisharati, a member of the Hindu school of Mathematics from Kerala. This is also an example where it was used in non-scientific work.

Thus the katapayadi system allows the author to represent large numbers using easy-to-remember words. It also has the flexibility to let the author pick an appropriate word for the context and one that fits the meter if it’s a poem.

During the time of Aryabhatta, there were at least three methods of writing numbers. Mathematicians like Varahamihira and Bhaskaracharya used a system called the bhoot samkhya. Aryabhatta, though, invented his own system, which was a new contribution.(The Aryabhata Number System)

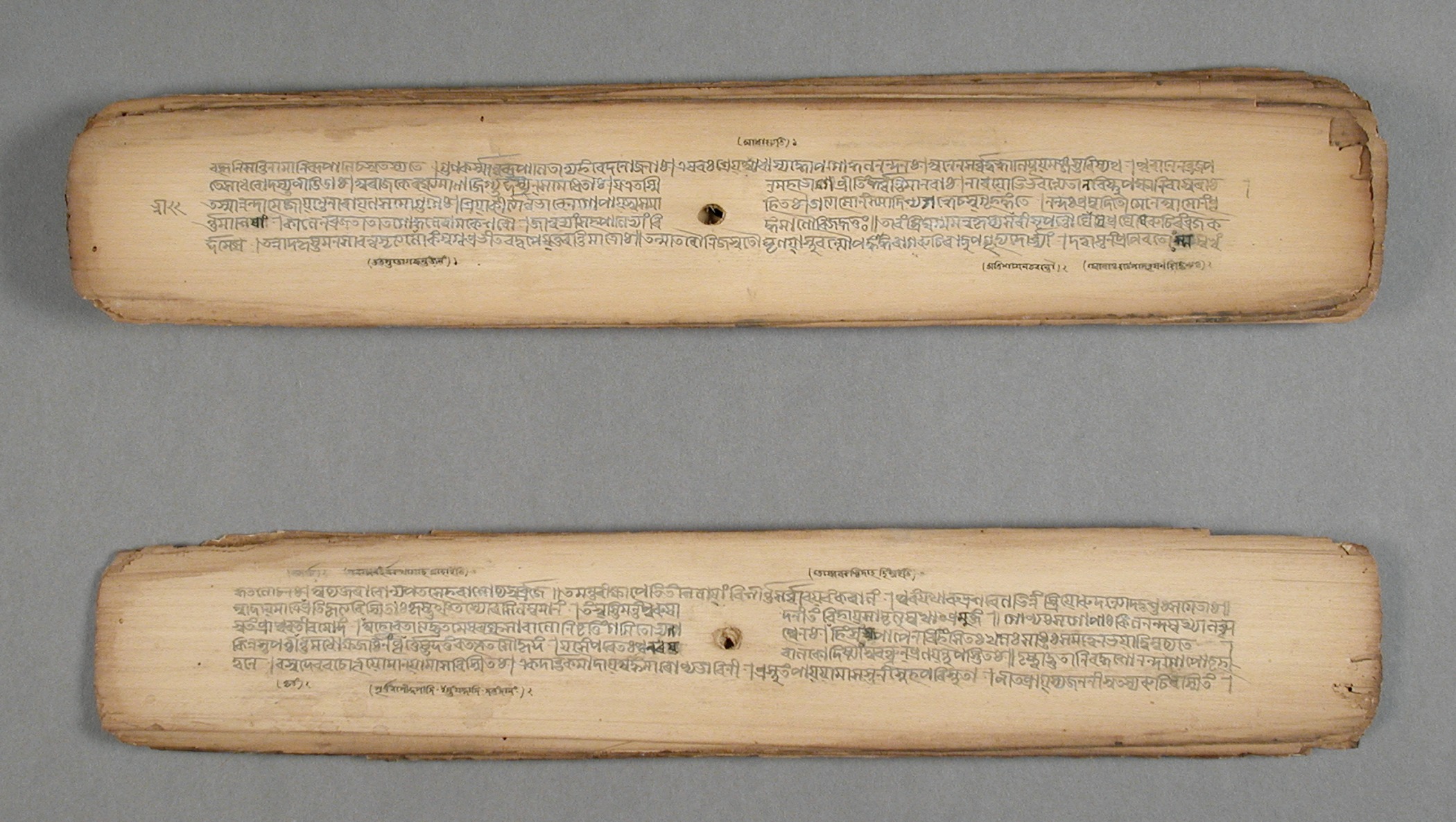

Katapayadi number system was primarily used by Hindu mathematicians and astronomers in Kerala. The fact that numbers can be converted to meaningful words that can be strung together helped Malayali mathematicians perform complicated calculations from memory. They computed eclipses, memorized the calculations using words, and committed to memory. This way, there was no dependency on books or tables. This system of memorization was prevalent till around 100 years back.

The book Moonwalking with Einstein talks about various techniques used by the ancients to memorize data. One of the techniques was called memory palace. The katapayadi system looks simpler as the data to commit to memory is that table.

Origins and Spread

If you ask, who started this number system, there are many answers. It’s possible that Vararuchi wrote them in Candra-vakyas in the fourth century. Aryabahata I, who lived 100 years after, was aware of it. It was then popularized in 683 CE in Kerala by Haridatta. ́Sankaranarayana ( 825–900 CE) mentions this name in his commentary on the Laghubhaskarıya of Bhaskara I. Subhash Kak argues that the the system is much older

Though the system originated in Kerala, it spread around India. Though it was well known in the northern part of India, it was not widely used. It spread from Kerala to Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry. That came due to their contact with Nilakanta Somayaji, another mathematician from the Madhava school. In Karnataka, Jains used it in their writing. Orissa has manuscripts that show usage of this system. Aryabhata II used this in the 10th century with some modifications. Bhaskara II used both Bhootsamkya system and Katapayadi system in his works.

This system was not used just in astronomy and mathematics but also in classifying music. For example, the 72 ragas were classified by musicologist Muddu Venkata Makki using the first two letters to indicate the serial number of the Melakartharagam. Thus Kanakangı shows the serial number 1, Rupavatı 12, Sanmukhapriya 56, or Rasikapriya 72.

You are too late if you think this system would help write something like Da Vinci Code. The National-Treasure-in-India script was done a few hundred years back. Ramacandra Vajapeyin, who lived in Uttar Pradesh, used this technique to forecast a dispute or war victory. His brother wrote a text to draw magic squares for therapeutic purposes.

Forgotten Mathematicians

I learned about the Hindu school of Mathematics (as opposed to the Jain school) from Kerala by reading A Passage to Infinity by George Gheverghese Joseph. Though there were few mathematicians in Kerala in the 9th, 12th, and 13th centuries, what is today called the Kerala School started with Madhava, who came from near modern-day Irinjalakuda. His achievements were phenomenal; they included calculating the exact position of the moon and what is now known as the Gregory series for the arctangent, Leibniz series for the pi and Newton power series for sine and cosine with great accuracy.

Some of these techniques were forgotten, but thanks to a renewed interest in Samskritam, there is a revival of knowledge. This whole article was triggered when I read the first chapter of my Samskrita Bharati book on sandhis which mentioned the katapayadi system.

Postscript

- If are you curious to know why Mahābhārata was called jaya, then read this article.

References:

- Vijayalekshmy M. “‘KATAPAYADI’ SYSTEM — A CONTRIBUTION OF MEDIEVAL KERALA TO ASTRONOMY AND MATHEMATICS.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 69, 2008, pp. 442–46, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44147207. Accessed 7 May 2022.

- Anusha, R., et al. “Coding the Encoded: Automatic Decryption of KaTapayAdi and AryabhaTa’s Systems of Numeration.” Current Science, vol. 112, no. 3, 2017, pp. 588–91, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24912445. Accessed 7 May 2022.

- Kak, Subhash. “INDIAN BINARY NUMBERS AND THE KAṬAPAYĀDI NOTATION.” Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, vol. 81, no. 1/4, 2000, pp. 269–72, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41694622. Accessed 7 May 2022.

- Iyer, P. R. Chidambara. “REVELATIONS OF THE FIRST STANZA OF THE MAHĀBHĀRATA.” Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, vol. 27, no. 1/2, 1946, pp. 83–101, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41784867. Accessed 7 May 2022.

- A. V. Raman, “The Katapayadi formula and the modern hashing technique,” in IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 49-52, Oct.-Dec. 1997, doi: 10.1109/85.627900.

When Duff first proposed this method, veteran missionaries did not find it appealing. Still he went ahead without any government support. Bengalis did not mind an English school, but had reservations about an English school where Bible was an important subject. This reservation made it difficult for Duff to get started; he could not even find a building to start his classes.

When Duff first proposed this method, veteran missionaries did not find it appealing. Still he went ahead without any government support. Bengalis did not mind an English school, but had reservations about an English school where Bible was an important subject. This reservation made it difficult for Duff to get started; he could not even find a building to start his classes.