The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century (Paperback), by Ross E. Dunn, 379 pages, University of California Press; 1 edition (December 9, 2004)

The first thing that Prof Matthew Herbst asks students to do in the introductory lecture of the series New Ideas/Clash of Cultures at University of California, San Diego is to draw a map of the world and label as many countries as possible. A minute later they are asked to keep their pens down and name the country at the centre of the map. Some have Italy, a few have North America, and some the Atlantic Ocean.

This instinctive action, which illustrates the cultural bias of historians, is amplified if education starts with the typical Western Civilization till 1600 followed by the Western Civilization since 1600 course. A student could thus specialise in the Ancient Near East with tangential knowledge about India, China, Africa, or the Muslim empires.

Affinity towards one’s homeland is natural, but it should be balanced with knowledge about other civilisations. It is natural that for Indians, the centre of their world is India, but when they read about the Buddha, knowledge of the Axial age — when Socrates, the Jewish prophets, and Confucius revolutionised thinking — gives better perspective. Such perspective provides awareness that the empiricism of John Locke and scepticism of David Hume could be derived from the dialogue between Indra and Prajapathi in Chandogya Upanishad. Proper context for local history will be obtained by taking an introductory course in World Civilisation instead of Western Civilisation, as well as by reading the works of ancient travellers like Ibn Battuta.

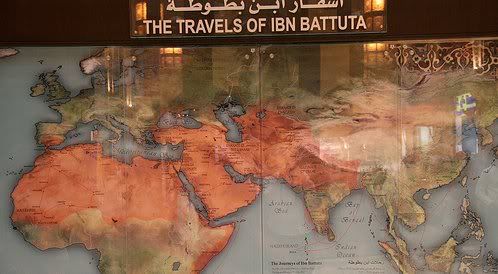

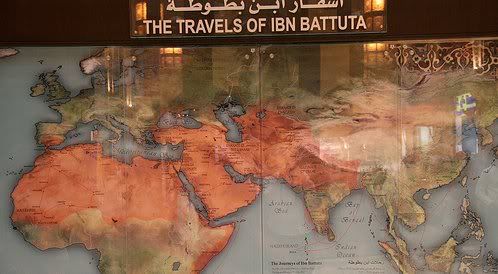

In 1325, this twenty-one year old Moroccan left home to perform the haj. In fact he visited Mecca four times—first from Morocco via North Africa, Egypt, Palestine and Syria, the second after visiting Iraq and Persia, the third after going down the Swahili coast up to Tanzania and the final one after visiting Anatolia, Delhi, Calicut, Maldives and China. When he returned to Morocco, surviving the Black Plague that devastated Europe, he had visited about forty countries in the modern map covering a distance of 117,000 km.

In 1325, this twenty-one year old Moroccan left home to perform the haj. In fact he visited Mecca four times—first from Morocco via North Africa, Egypt, Palestine and Syria, the second after visiting Iraq and Persia, the third after going down the Swahili coast up to Tanzania and the final one after visiting Anatolia, Delhi, Calicut, Maldives and China. When he returned to Morocco, surviving the Black Plague that devastated Europe, he had visited about forty countries in the modern map covering a distance of 117,000 km.

Settling down in Tangier he collaborated with a young literary scholar, Ibn Juzayy, to compose the rihla—a book of travels in Arabic literature—about his impressions of all the countries and his experience which included working as a judge for Mohammed bin Tughluq, becoming penniless near the Doab, and attempting a coup in Maldives.

Since Ibn Battuta wrote his rihla towards the end of his itinerant career, some details are incorrect and fuzzy; after visiting Constantinople, Ibn Battuta was impressed by the markets, monasteries and the Genoese colony of Galata while in reality, by that time, it was a city on the decline. Also his book is not an encyclopedia; he wrote about things which fascinated him, like saints, life among the upper crust of society, and Muslim culture.

So using the rihla as spine, Ross E Dunn has fleshed out this book by providing the history of each city that Ibn Battuta visited. The chapter on Anatolia provides a brief history of the transformation of a country of Greek and Armenian Christians into Turkey and the sections on Cairo and Delhi provides background information on how they both rose to prominence, thanks to the Mongol empire. Since Ibn Battuta’s objects of fascination were few, Dr Dunn juxtaposes the missing pieces from other history books and writings from other travellers like Simon Semeonis, Ludolph von Suchem, and Ibn Jubayr, making this book comprehensive.

Ibn Battuta’s World

Some time after the first haj Ibn Battuta heard about India’s riches and wanted to seek employment there. He already had exposure to Indians; some selling drugs and food items in Mecca, some as pages accompanying Princess Bayalun of the Golden Horde, and some scholars in Oman. He knew that Indian ships sailed to Aden regularly. He also knew that the Delhi Sultanate welcomed foreigners and paid well.

Some time after the first haj Ibn Battuta heard about India’s riches and wanted to seek employment there. He already had exposure to Indians; some selling drugs and food items in Mecca, some as pages accompanying Princess Bayalun of the Golden Horde, and some scholars in Oman. He knew that Indian ships sailed to Aden regularly. He also knew that the Delhi Sultanate welcomed foreigners and paid well.

It is interesting to contrast some of the places Ibn Battuta visited with their current state. Mogadishu, currently invokes the images of civil war, militias and poverty, but at the time of Ibn Battuta’s visit, it was one of the richest ports owing to the connections with the Horn of Africa and Ethiopia. Ibn Battuta met the ruler, Abu Bakr, who wore a “robe of green Jerusalem stuff” above “fine loose robes of Egypt with a wrapper of silk.” During a meal of chicken, meat, fish, green ginger, mangoes and pickled lemon, he observed that a single resident of Mogadishu ate more than a whole company of visitors.

While the Mongols had reduced Baghdad to a small provincial town, Cairo was prospering under the Mamluk Sultanate—members of a slave dynasty—due to the Red Sea trade. Jerusalem, which was under Mamluk control, was a small town of no great importance; Ibn Battuta spent a week there meeting various scholars and Sufi masters. By the time he arrived in Delhi, Mohammed bin Tughluq, who had succeeded a Slave Dynasty, had finished his experiment in shifting capitals. A seven year drought and the first of the twenty-two rebellions that would bring his downfall was about to start.

On his first visit, the sultan’s mother gave Ibn Battuta 2000 silver dinars. Even before he got the job of the judge, Tughluq ordered him to be paid 5000 silver dinars and the revenue from two villages. On his appointment, he got 12,000 dinars as perquisite with an annual salary of 12,000 dinars. According to Dunn, at that time an average Hindu family lived on 5 dinars per month; a soldier, 20.

Even though he was rich, the cost of living in Delhi was high. The hamster that kept the Delhi’s economic wheel turning, much like the present, was sycophancy. Nobles borrowed money to buy expensive gifts for the sultan and other nobles, who then reciprocated with gifts of higher value. Soon Ibn Battuta amassed debts of more than 55,000 dinars to get out of which, quite interestingly, he composed an ode to the Sultan.

Also he faced first hand the job risks in working with a pixilated Sultan. Tughluq took umbrage at Ibn Battuta’s association with a Sufi ascetic who had fallen out of favour. Tughluq first got the ascetic’s beard plucked hair by hair, then later tortured and beheaded him. Ibn Battuta was put under house arrest for nine days and expected to be executed. Surprisingly he was freed and entrusted with a mission to China.

Arriving in Calicut and Quilon on his way to China as the Mughal emissary to the Mongol court carrying a gift of 200 Hindu slaves, he found that the entire trade of the Malabar and Coromandel coast was controlled by Muslims. He also found that the Hindu rulers of those provinces allowed Muslims to worship as they pleased and encouraged these trade communities. Also, similar to the frequent battles between the countries on the African coast, battles among small provinces along the Indian west coast was also common and Ibn Battuta participated in the battle by Honavar against Sandapur (Goa).

Arriving in Calicut and Quilon on his way to China as the Mughal emissary to the Mongol court carrying a gift of 200 Hindu slaves, he found that the entire trade of the Malabar and Coromandel coast was controlled by Muslims. He also found that the Hindu rulers of those provinces allowed Muslims to worship as they pleased and encouraged these trade communities. Also, similar to the frequent battles between the countries on the African coast, battles among small provinces along the Indian west coast was also common and Ibn Battuta participated in the battle by Honavar against Sandapur (Goa).

Ibn Battuta’s travels showcase the importance of Muslim trade networks and the prosperity it bought to the trading communities in India and elsewhere. He travelled during a period of relative calm; the crusades were over, the Mongols were Islamised and the Muslim caravan routes throbbed with activity carrying not just merchants, but scholars, craftsmen, Sufis and converts. Thus a Muslim grandee seized by wanderlust could travel through Dar al-Islam staying in mosques, or with the scholars, kings, and saints receiving gifts of robes, horses and camels.

The relative peace during Ibn Battuta’s time soon changed. In China, Genghis Khan’s heir fled with his entire court unable to halt the advance of the rebels. The Ottoman Turks captured Constantinople and turned the Hagia Sophia into a mosque. Timur invaded Delhi and by his own account killed 10,000 infidels in an hour. The most important event happened, a century later, in the Malabar coast with the arrival of Vasco da Gama’s fleet. This was not just a great navigational feat, but a major geo-political event by which Europeans cut off the Muslim middlemen.

Dr. Dunn’s book presents Ibn Battuta’s world not in isolation, but in a global context helping us better understand the world of 14th century. It is not surprising that this book was required reading in Prof. Herbst’s class.

Image Credits: cgsheldon, lloydi,

mckaysavage

mckaysavage

(This review appeared in the June 2009 edition of Pragati)

Some time after the first haj Ibn Battuta heard about India’s riches and wanted to seek employment there. He already had exposure to Indians; some selling drugs and food items in Mecca, some as pages accompanying Princess Bayalun of the Golden Horde, and some scholars in Oman. He knew that Indian ships sailed to Aden regularly. He also knew that the Delhi Sultanate welcomed foreigners and paid well.

Some time after the first haj Ibn Battuta heard about India’s riches and wanted to seek employment there. He already had exposure to Indians; some selling drugs and food items in Mecca, some as pages accompanying Princess Bayalun of the Golden Horde, and some scholars in Oman. He knew that Indian ships sailed to Aden regularly. He also knew that the Delhi Sultanate welcomed foreigners and paid well. Arriving in Calicut and Quilon on his way to China as the Mughal emissary to the Mongol court carrying a gift of 200 Hindu slaves, he found that the entire trade of the Malabar and Coromandel coast was controlled by Muslims. He also found that the Hindu rulers of those provinces allowed Muslims to worship as they pleased and encouraged these trade communities. Also, similar to the frequent battles between the countries on the African coast, battles among small provinces along the Indian west coast was also common and Ibn Battuta participated in the battle by Honavar against Sandapur (Goa).

Arriving in Calicut and Quilon on his way to China as the Mughal emissary to the Mongol court carrying a gift of 200 Hindu slaves, he found that the entire trade of the Malabar and Coromandel coast was controlled by Muslims. He also found that the Hindu rulers of those provinces allowed Muslims to worship as they pleased and encouraged these trade communities. Also, similar to the frequent battles between the countries on the African coast, battles among small provinces along the Indian west coast was also common and Ibn Battuta participated in the battle by Honavar against Sandapur (Goa).