(This op-ed was published in Jan 25, 2009 edition of Mail Today/ PDF)

To commemorate the International Year of Astronomy in 2009, P Govinda Pillai, a Communist Party of India (Marxist) ideologue, in an article in the Malayalam newspaper Mathruboomi, examined the legacy of Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler. He also bought out an important topic – Eurocentrism in history writing – due to which we know about the work done on telescopes by Galileo, Hans Lippershey and Roger Bacon, but almost nothing by the Arab scientist al-Hassan.

Mr. Pillai stopped there. He wrote nothing about the contributions of mathematicians and astronomers from his state, Kerala, in developing the heliocentric model and calculating planetary orbits. It is not Mr. Pillai alone who is at fault. This apathy, this ignorance, this refusal to acknowledge Indian contributions — all point to a deep malaise in our historical studies. For perspective on this issue, we need to understand the contributions of Indian astronomers and decide if we should be like Confucians during the time of the Ming dynasty or 21st century Peruvian archaeologists.

The Kerala School of Mathematics

In 1832, a paper, “On the Hindu quadrature of a circle”, was read at the Royal Asiatic Society. This paper by Charles M. Whish of the East Indian Company Civil Service described eight mathematical series quoting from a text called Tantra Sangraham (1500 CE) which he had discovered in Kerala. These series were also mentioned in Yukti Dipika by Sankara Variyar and Yukti-Bhasa by Jyestadevan; both those authors had learned mathematics and astronomy from Kellalur Nilakanta Somayaji, the author of Tantra Sangraham. Some of those series were linked to Madhavan of Sangramagramam (1340-1425 CE). These mathematicians who lived between the 14th and 16th centuries formed the Kerala School of Mathematics and were proof that Indian mathematics did not vanish after Bhaskaracharya.

The importance of the Kerala school can be appreciated only by understanding the Copernican revolution. The contribution of Copernicus was two fold: first he improved

the mathematics behind the Ptolemaic system and second, changed the model from geocentric to heliocentric. The heliocentric model was proposed as early as the third century BCE by the Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos and so it is the math that made the difference.

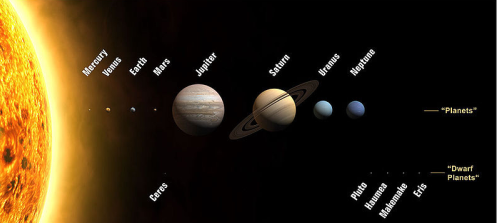

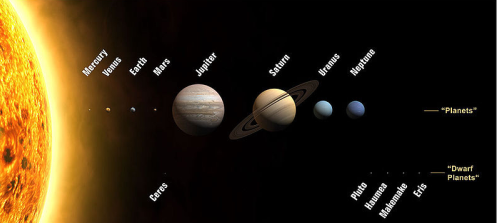

In his Tantra Sangraham, Nilakanta revised the Indian planetary model for the interior planets, Mercury and Venus and for this he formulated equations to find the center of the planets better than both Islamic and European traditions. He also described the planetary motion in which Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn moved in eccentric orbits around the Sun, which in turn went around the Earth. Till Nilakanta, the Indian planetary theory had different rules for calculating latitudes for interior and exterior planets. Nilakanta provided a unified rule. The heliocentric model of Copernicus did not alter the computational scheme for interior planets; it would have to wait till Kepler (who wrote horoscopes to supplement his income).

In his Tantra Sangraham, Nilakanta revised the Indian planetary model for the interior planets, Mercury and Venus and for this he formulated equations to find the center of the planets better than both Islamic and European traditions. He also described the planetary motion in which Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn moved in eccentric orbits around the Sun, which in turn went around the Earth. Till Nilakanta, the Indian planetary theory had different rules for calculating latitudes for interior and exterior planets. Nilakanta provided a unified rule. The heliocentric model of Copernicus did not alter the computational scheme for interior planets; it would have to wait till Kepler (who wrote horoscopes to supplement his income).

In their propensity to solve astronomical problems, mathematicians of the Kerala school developed concepts like Gregory’s series and the Leibniz’s series. The hallmark of earlier texts, like those of Madhava, were instructions and results without proofs or explanations. It is believed that the proofs and explanations were passed orally and hence rarely recorded. Yuktibhasha, the text written by Jyesthadeva, contain proofs of the theorems and the derivations of the rules, making it a complete text of mathematical analysis and possibly the first calculus text.

Lessons from Peru

Our education system, based on content from Western textbooks, have rarely questioned Western accomplishments. But Peruvians thought differently. When Peruvian archaeologists revisited the history written by the victors they discovered that the romantic tales woven by the Conquistadors were – well, tales. According to the original story, Francisco Pizarro, a Spaniard arrived in Peru in 1532 with few hundred men. Few weeks after their arrival, in a surprise attack, they killed the Inca king Atahualpa and took Cusco, the Inca capital. Four years later the Inca rebellion attacked Cusco and the new city of Lima.

On August 10, 1536, while Copernicus and the Kerala school were revolutionizing the world of astronomy half a world away, Francisco Pizzaro watched as tens of thousands of Incas closed in on Lima. With just a few hundred troops, Pizzaro had to come up with a strategy for survival. The Spaniards lead a cavalry attack and first killed the Inca general and his captains. Devoid of leadership the Incas scattered and once again the Spaniards won.

Recent archaeological excavations found a different version of this story. Out of the many skeletons found in the grave near Lima, only three were found to be killed by Spanish weapons; the rest by Incas. A testimony by Incas who were present in the battle was found in the Archive of the Franciscans at the Convent of San Francisco de Lima, which mentioned that it was not a great battle, but just a few skirmishes. Pizzaro was helped by a large army of Indian allies and the battle was not between the Spaniards and Incas, but between two Inca groups. It was also found that size of rebels were not in tens of thousands, but in thousands and there was no cavalry charge.

Thanks to the work of native archaeologists dramatic accounts of a small band of heroic Europeans subduing the Incas has a new narrative.

Lessons from China

Instead of following such examples and popularizing the work of Indian mathematicians, we have been behaving like Confucians at the court of the 15th century Ming emperor Zhu Di who erased evidence of the large fleets that sailed as far as the Swahili coast. While the world knows about the accomplishments of Europeans like Vasco da Gama, Columbus, Magellan and Francis Drake, little is known about Zheng He who arrived in Calicut eighty years before da Gama commanding a fleet of three hundred ships carrying 28,000 men; Vasco da Gama arrived with three ships and less than two hundred men.

Instead of following such examples and popularizing the work of Indian mathematicians, we have been behaving like Confucians at the court of the 15th century Ming emperor Zhu Di who erased evidence of the large fleets that sailed as far as the Swahili coast. While the world knows about the accomplishments of Europeans like Vasco da Gama, Columbus, Magellan and Francis Drake, little is known about Zheng He who arrived in Calicut eighty years before da Gama commanding a fleet of three hundred ships carrying 28,000 men; Vasco da Gama arrived with three ships and less than two hundred men.

Between 1405 to 1433, Zheng He’s fleet made seven voyages —- three to India, one to Persian Gulf and three to the African coast — trading, transporting ambassadors, and establishing Chinese colonies. Following the death of the emperor who commissioned these voyages, the Confucians at the court gained influence. Confucius thought that foreign travel interfered with family obligations and Confucians wanted to curtail the ambitious sailors and the prosperous merchants.

So ships were let to rot in the port and the logs books and maps were destroyed. The construction of any ship with more than two masts was considered a capital offense. A major attempt at erasing a proud chapter in their history was done by the natives themselves.

Appreciating our stars

The goal is not to diminish the accomplishments of Copernicus or Galileo but to note that no less important accomplishments were achieved by the Kerala school either before or around the same time. Interestingly in the West, Copernican revolution was considered a movement into science to which the Church, obstinate in religious dogma, would take umbrage. In India no one was burned at the stake or put under house arrest for proposing a heliocentric model.

Instead of accepting the astronomical concepts of the Church on faith, Galileo investigated them and found new truths. Extrapolating that to historical studies we need to critically examine the Eurocentric history like the Peruvians and popularize the work of our ancestors. In this International year of astronomy, if we do not inform everyone about our great astronomers, who will ?

Postscript: In the midst of all this Eurocentric history, as a surprising exception to the norm, the only educational institution where one can take an elective course in The Pre-History of Calculus and Celestial Mechanics in Medieval Kerala is Canisius College, New York.

References: This credit for this article goes to Ranjith, a reader of this blog. He alerted me to Govinda Pillai’s article and then sent various research papers and articles about the Kerala School. He made me read Modification of the earlier Indian planetary theory by the Kerala astronomers, 500 years of Tantrasangraha, Madhavan, the father of analysis, Whish’s showroom revisited and The Pre-History of Calculus and Celestial Mechanics in Medieval Kerala.

Dick Teresi’s book Lost Discoveries, which I first read in 2003, covers the ancient roots of modern science and has sections on Indian mathematicians and astronomers. I remember buying The Crest of the Peacock and lending it to a mathematician friend; the book is now inside a singularity. The Great Inca rebellion was covered in the excellent PBS documentary of the same name. References for Zheng He can be found in an earlier article. In 2000, the University of Madras organized a conference to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Tantrasangraha. The papers presented at this conference can be found in 500 Years of Tantrasangraha

and lending it to a mathematician friend; the book is now inside a singularity. The Great Inca rebellion was covered in the excellent PBS documentary of the same name. References for Zheng He can be found in an earlier article. In 2000, the University of Madras organized a conference to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Tantrasangraha. The papers presented at this conference can be found in 500 Years of Tantrasangraha

Finally, Rajiv Malhotra on Eurocentrism of Hegel, Marx, Mueller, Monier Williams, Husserl.

(images via wikipedia and indiaclub)

For Dubois, these Hindu fables were absurd. Before presenting his theory, he first dismissed two other ideas. The first one claimed that Egyptian king Sesostris conquered land till the Ganges; the second, that the caste system was obtained from the Arabs.

For Dubois, these Hindu fables were absurd. Before presenting his theory, he first dismissed two other ideas. The first one claimed that Egyptian king Sesostris conquered land till the Ganges; the second, that the caste system was obtained from the Arabs.

In his Tantra Sangraham, Nilakanta revised the Indian planetary model for the interior planets, Mercury and Venus and for this he formulated equations to find the center of the planets better than both Islamic and European traditions. He also described the planetary motion in which Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn moved in eccentric orbits around the Sun, which in turn went around the Earth. Till Nilakanta, the Indian planetary theory had different rules for calculating latitudes for interior and exterior planets. Nilakanta provided a unified rule. The heliocentric model of Copernicus did not alter the computational scheme for interior planets; it would have to wait till Kepler (who wrote horoscopes to supplement his income).

In his Tantra Sangraham, Nilakanta revised the Indian planetary model for the interior planets, Mercury and Venus and for this he formulated equations to find the center of the planets better than both Islamic and European traditions. He also described the planetary motion in which Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn moved in eccentric orbits around the Sun, which in turn went around the Earth. Till Nilakanta, the Indian planetary theory had different rules for calculating latitudes for interior and exterior planets. Nilakanta provided a unified rule. The heliocentric model of Copernicus did not alter the computational scheme for interior planets; it would have to wait till Kepler (who wrote horoscopes to supplement his income). Instead of following such examples and popularizing the work of Indian mathematicians, we have been behaving like Confucians at the court of the 15th century Ming emperor Zhu Di who erased evidence of the large fleets that sailed as far as the Swahili coast. While the world knows about the accomplishments of Europeans like Vasco da Gama, Columbus, Magellan and Francis Drake, little is known about

Instead of following such examples and popularizing the work of Indian mathematicians, we have been behaving like Confucians at the court of the 15th century Ming emperor Zhu Di who erased evidence of the large fleets that sailed as far as the Swahili coast. While the world knows about the accomplishments of Europeans like Vasco da Gama, Columbus, Magellan and Francis Drake, little is known about